The Human Scale: Part III

Even Further Defintions of the Human Scale as it relates to town and cities

The Human Scale—Beyond the Spatial

Previously I attempted to define the human scale from the parameters of the spatial, in the horizontal and the vertical, and in the matter of growth. To recap: the human scale, as applied to the town or city, is where the average person is able to get around on foot without relying on machines: cars, elevators, etc. The human scaled town or city grows organically: as it reaches its mature size and form, further growth occurs through replication, like humans.

Human Scaled Materials

In this part I will discuss how the human scale applies to the actual materials used in the construction of a town.

Human scaled materials are those that can be sourced, used, maintained, dismantled, and reused by hand.

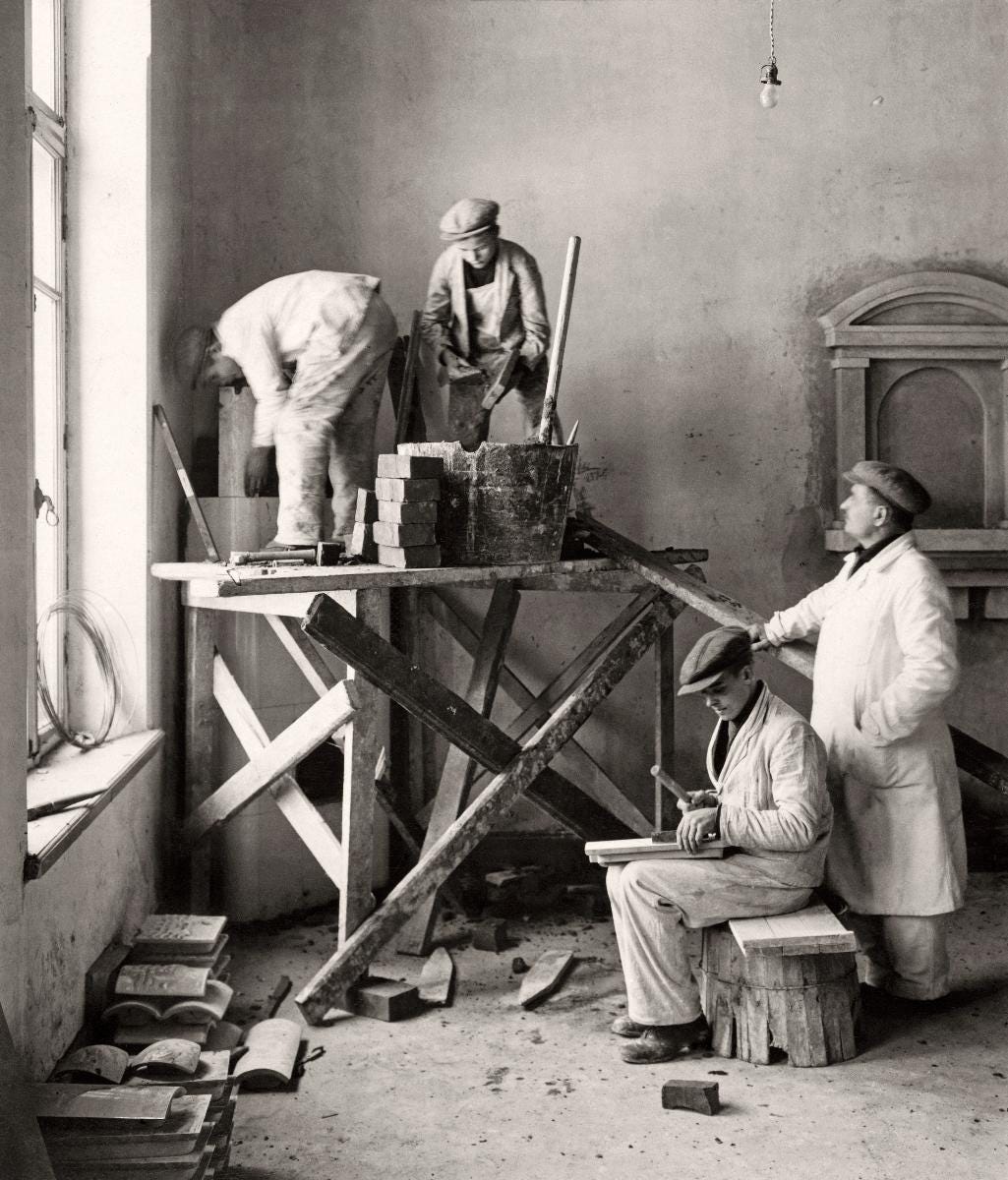

Take the humble brick for example, maybe the foremost material for building towns and cities around the world and throughout history (especially in places that are not particularly prone to earthquakes). It is of a size that easily fits in an adult mason’s hand, leaving the other hand free for a trowel with which to apply the mortar. Laying brick requires no protective gear, no chemicals or machinery, and the skills needed can be taught anywhere to almost anyone.

The organization of labor in laying brick is also eminently human scaled. Traditionally a team of skilled masons, from apprentices to a master, are supplied with bricks and mortar by one unskilled hod carrier1 per mason. It makes for a smooth, steady rhythm of work. It is easy to calculate the amount of time and materials required, delays and hold ups are rare because once work starts there is no need to wait for special tools or faraway factory made parts, no rented equipment standing around costing money even when not in use. The building grows steadily and safely. Contractors and customers can be confident in the fair pricing of the work and at each day progress is easily verified. Local or regional standards are a reliable guide to how much and what quality work can be expected. Material use is easy to keep track of, keeping waste or pilfering and spillage to a minimum.

The opposite of human scaled building materials and tools are those that require special equipment to move and install, or sourced outside of the nearby region or even on different continents. Often requiring specialists at that particular product or material. In practice we see this when encountering “pre-manufactured components”: i.e., building vs. assembling. Non-human scaled materials sometimes require protective gear (goggles, gloves, protective suits, ear protectors etc.), are toxic to some degree or impossible to recycle or reuse. Usually they come with installation requirements so complicated and specific that any new build is guaranteed to contain any number of building errors of various severity and urgency.

In small building projects, a hold up in the supply chain or the building process can mean that building halts while expenses keep running. In larger projects delays can be exponentially more costly. This is one reason large modern building projects never finish on budget: it is simply impossible to foresee or allow for the countless problems that can occur, especially when the supply chain is global.

Human Scaled Materials—Maintenance and Recycling

Human scaled materials can be repaired or maintained by human hands. Failure points in materials are visible to the naked eye and piecemeal repairs can be undertaken as necessary. Even when entire building sections are removed or exchanged, materials that have survived well can be salvaged and reused. They are relatively fault tolerant.2

They also recycle well. Solid log or timber frame buildings are fully recyclable3 and can even be dismantled and reassembled elsewhere, put in storage for decades or used for spare parts in new or bigger building projects. In brick buildings where lime mortar was used the bricks can easily be hacked off, cleaned up and reused. The waste mortar can be crushed and recycled as an agricultural soil conditioner or crushed and used as aggregate in new lime mortars4. All of this can be done by hand if necessary.

On the other hand, non-human scaled materials are usually destined for the landfill.

The use of non-human scaled materials is not only a problem in new building projects but also in the sale of finished developments or older houses. There are often no non-destructive methods of checking the soundness of roofs and walls and this can lead to prolonged and difficult court cases, both on an individual basis and across entire industries or regions. Newspapers abound with articles on the wonder materials or building methods of yesteryear that failed so spectacularly they are now the subject of scandal and decade long court cases affecting tens of thousands of families.5 With the original contractors out of business, poor or non-existing documentation and discontinued building materials and lapsed warranties, it adds unnecessary hardships and financial risk to both buyer and seller.

Labor and Costs: Building Wealth

When building with human scaled materials a large part of the budget goes to craftsmen, artisans and labor, and this is good. Local wages goes to locals, your neighbors and friends, who tend to use the money locally. A mason or carpenter can not easily dodge taxes or use accounting tricks to hide profits in off-shore accounts, so their paid taxes will hopefully be used locally for projects that will benefit everyone in your town.

This is a fool proof method of building local wealth and long-lasting value: brick by brick. Non-human scaled building projects has similar building costs, but a far larger part of the budget goes to faraway factories and corporations, draining your town and community of expertise and wealth for the benefit of no-one you have ever met, nor ever will, meet.

In the next part of “The Human Scaled metric when applying it to towns and cities” I will write about the temporal aspect: how does a human scaled town perpetuate itself over time?

A hod is a three sided tool on top of a pole used for carrying bricks. The laborer employed for the job is called a hod carrier. In owner built projects it is a good job for fit but otherwise unskilled family members and friends, helping to keep down the costs of labor in building projects.

Fault tolerant designs or materials are those that can continue function (even at a reduced level) when some part or aspect of it fails. In buildings this means that a blocked weep hole (a tiny opening where water and vapor that has entered the wall is allowed to exit safely) in a brick wall will not invalidate the entire design as there are several other weep holes in the same wall. A fault intolerant design or material is for example a wall covered in “exterior insulation and finish systems” where a single crack invisible to the naked eye could lead to water infiltration that rots the entire wall right through.

Recycled: reused for the same purpose. A wine bottle is washed and used again.

Upcycled: repurposed for something better. A wine bottle is washed and used to make a bottle ship.

Downcycled: the reuse is far less valuable than the original use. A wine bottle is crushed to make road aggregate.

If you used environmentally disastrous cement mortar on the other, not only does it ruin the bricks (even the ones that survive sticks to the cement so badly that you can’t reuse them), the cement mortar itself is at best gathered and put in a landfill. At worst fly-tipped.

I am not arguing against innovation or trying out new products and methods, which is fine and if you are building for yourself, but can lead to tragedy if you adapt a poorly understood material or a difficult to execute building practice on an industry-wide scale. We do not experiment in building homes and cities for the same reasons that we do not put experimental jet aircraft in regular airline traffic. Just because a recent material or building method has been approved or “everyone’s doing it” does not mean that it is safe or good. Look at the 19th century arsenic paints, early 20th century asbestos and the late 20th century exterior insulation and finish systems (EIFS), that we are still paying dearly for.

In other cases we build things simply because everyone else seems to be doing it: whether it is the best solution in each particular case is irrelevant. Case in point being the concrete slab foundation (the pad-fab).